Is it over?

Is It Over?

It seems like just yesterday that you could buy a pint of Stella for $7 or so. Now, more often than not, it is closer to $10. Yep, inflation. It is kind of like a tax on doing things, as just about everything has cost more over the past few years. Hop on a flight, eat at a nice restaurant, refinance your mortgage, the list goes on. With the benefit of hindsight, the current higher inflationary

environment can be blamed on a few pretty big factors. Changes in behaviour during and coming out of the pandemic blew up supply changes, as capacity was unable to keep pace with demand. Then, of course, unprecedented money printing magnified the situation, as it made everyone wealthier and more willing to pay $10 for a pint.

Of course, the textbook solution is to raise interest rates, which is clearly occurring around the world. These monetary policy shifts are effective but do work with variable lags. Making those lags longer, or even temporally offsetting them, was fiscal policy. It doesn’t take an economist to understand if the monetary policy is trying to slow the economy to tame inflation; materially

elevated fiscal spending in an economy that is still growing at a decent pace is counterproductive for the inflation fight.

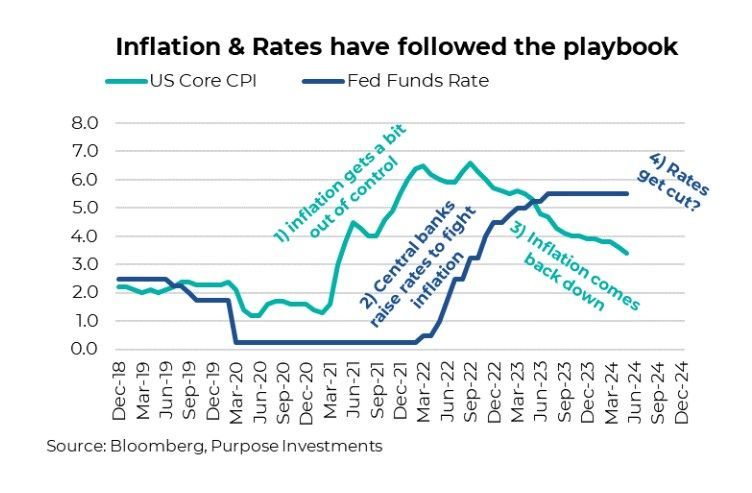

Despite contrary policies, perhaps motivated by short-term thinking (or upcoming elections), inflation has taken a decent turn down and continues to cool – but clearly, not in a straight line. You can note a quicker decline in the greenish line tracking U.S. year-over-year core inflation with the latest reading after a period where little progress was made. This chart really goes back to show how inflation got started. It was initially called ‘transitory,’ and then, finally, central banks jumped into action coincidentally when inflation had already peaked. Rarely ahead of the curve, those central bankers. Inflation declined a good amount in 2023, but the previous few months in 2024 showed it picking up or being much more sticky. This latest reading has things cooling again, which is good news.

The above is U.S. inflation, but the pattern is similar around the world for the most part. Inflation and the economy in Canada have cooled enough to open the door for the Bank of Canada to cut. In fact, the number of central banks cutting rates has been on the rise, including some of the biggies like the BoC and ECB. We will talk more about U.S. inflation simply because that is what moves global markets more.

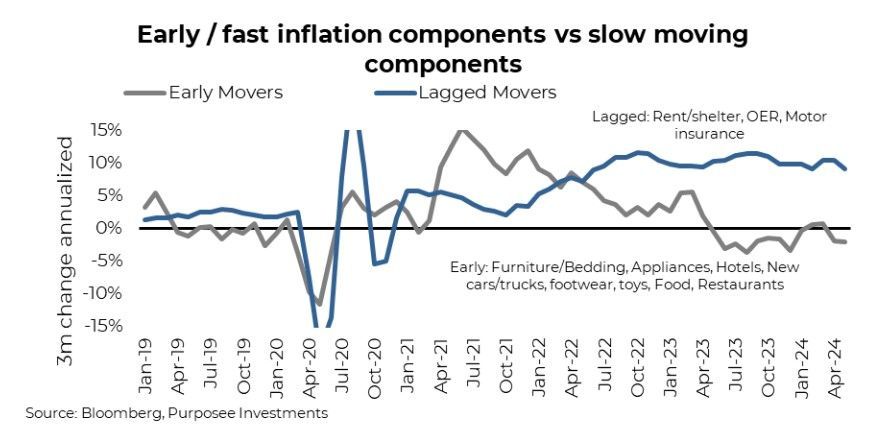

The fast or early movers in the CPI data have been improving for some time. These are the categories of CPI that simply change faster, as other components are much slower to react to changes in behaviour. Many goods categories, such as hotels, autos, and restaurants, are examples of areas of the economy that change prices rather fluidly. Rent, owner-occupied rent, and insurance are examples of areas where prices change very slowly or are even lagged in their reaction. Rents often don’t reset until the end of a lease and are further slowed by rent controls. Insurance, too, doesn’t reset often, so changes in actual prices take time to show up in the aggregate data.

New Paragraph